Flavour-driven sustainability

This essay is adapted from a presentation that Kim gave at the Baltic Gastro Summit in Vilnius, Lithuania in May 2025.

Table of Contents

i. Reframing sustainability as an opportunity

Sustainability means many different things to different people. Regardless of which definition you use, the UN defines it as ‘meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’. The team and I find this a pretty solid starting point.

However you define sustainability, for many people it can sometimes feel like a heavy word associated with sacrifice, guilt, and loss of pleasure, flavour, tradition and luxury. But sustainability need not be about sacrifice. Instead, it can be an opportunity.

In this article, I use three case studies—bread, fish and coffee, chosen for their relevance to the food cultures of both Lithuania and Denmark—to demonstrate the different opportunities that flavour-driven sustainability can present to chefs, namely:

Influencing industry and advocating broader food system transformation;

Enriching food culture through innovations that build on traditions;

Getting more from less.

I illustrate these three opportunities and case studies by exploring traditions of Lithuania (bread), developing a beloved dish of Denmark (fish), and drawing on experience from my time living in Japan (coffee).

ii. Bread

Bread is a near-universal staple food. It holds cultural, religious and economic significance that few other foods do. In Lithuania, where I delivered the talk this article is based upon, bread is deeply ingrained in the culture and is the subject of many proverbs. Whatever is happening in a Lithuanian’s life, it can probably be explained with bread. Nevertheless, there and elsewhere, bread is wasted to an incredible extent.

Lithuanian bread proverbs. Screenshot taken from Kim’s presentation.

Traditional approaches to upcycling emerged long ago in response.¹ Gira, a type of kvass, is a popular carbonated beverage in Lithuania, made by fermenting stale rye bread soaked in water with yeast, sometimes with fruits or spices. Even though it's a great example of upcycling, making gira also produces a by-product, the solids left after the liquids are removed.

Today, chefs can turn this problem of waste into an opportunity by harnessing their creativity. I wondered what I could do with the solid by-product of making gira. Some of the extra ingredients I was able to make are shown in Table 1.

| By-product description | Tasting notes | Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Untreated bread pulp, the immediate by-product after making gira. | Bready, yeasty and beery. | Base flavour in sauces and braises; desserts; eternal bread. |

| Post-gira bread pulp is heat-treated at 60°C for 24 hours. This kills the yeast, which then starts to autolyse, releasing enzymes that digest protein (its own and that in the bread). | Rich and meaty with lots of umami and kokumi. Less raw beer, more developed roundness. | Flavour enhancer for sauces, farces or mousses; doughs or pastries; miso or liquid condiments. |

| Heat-treated bread pulp is used to hydrate plant protein, which is then used as a substrate for fungal fermentation. | Rich and meaty with lots of umami and kokumi. No raw beer, more developed roundness, light fungal flavour. | Alternative proteins; doughs or pastries; miso or liquid condiments. |

Table 1: Different ways to upcycle the by-product of making gira

I took this final protein-rich ingredient and went one step further, making a burger out of it.

Fungal bread burger served with a glass of gira that it came from

This burger was delicious: meaty, rich, juicy, full of umami, and it fulfilled the textural needs expected of a burger. It didn’t taste exactly like a beef burger, but it doesn’t need to. It stands up as its own thing. It’s the type of product that should be more widely available, as it's something people wouldn’t need to be guilt-tripped to eat.

Importantly, in our opinion, it tasted better than a McDonald’s burger. That might sound like faint praise, but McDonald’s sells more than 270,000 burgers every hour worldwide. However you feel about their food, the fact is that they feed a lot of people. If an alternative like this bread burger replaced even a fraction of those beef burgers, the impact would be enormous. This bread burger would likely have a much lower environmental impact than beef does.² That’s not to say that bread burgers and similar products should replace all meat. There’s absolutely room for both. But replacing mass-produced fast food with better-tasting upcycled alternatives seems like an easy win. If that gives more space for ‘less but better meat’ elsewhere, we can still enjoy good quality meat in other contexts. But eating more burgers wouldn’t feel like a sacrifice, because they actually taste better than McDonald’s anyway.

This might be contentious, but I’d argue that big food companies like McDonald’s don’t create culture. They buy it. Whether through slick marketing, celebrity endorsements or crucially, collaborations with chefs. Because chefs themselves do create culture. By embracing opportunities like this, chefs can shape what industry pays attention to. If something is good enough, Big Food will eventually come knocking. And that can lead to real change.

Another example of a chef’s power to enact bigger change is the Salty Caramel Sourdough ice cream that I co-developed for Hansen’s (a popular Danish ice cream brand) during my time as head of R&D at Restaurant Amass. Originally developed as a fun promotion, it has since become a permanent flavour for the ice cream brand. Products like this help generate conversations with the public about our wasteful food system and the possibilities of upcycling. Except rather than having that conversation with a few dozen restaurant guests each night, this ice cream helps trigger those same conversations tens of thousands of times. This all came about from a restaurant’s pursuit of flavour and sustainability.

Ice cream made from waste bread

Sustainability doesn’t have to be about sacrifice; it’s an opportunity for chefs to have a say in food system transformation.

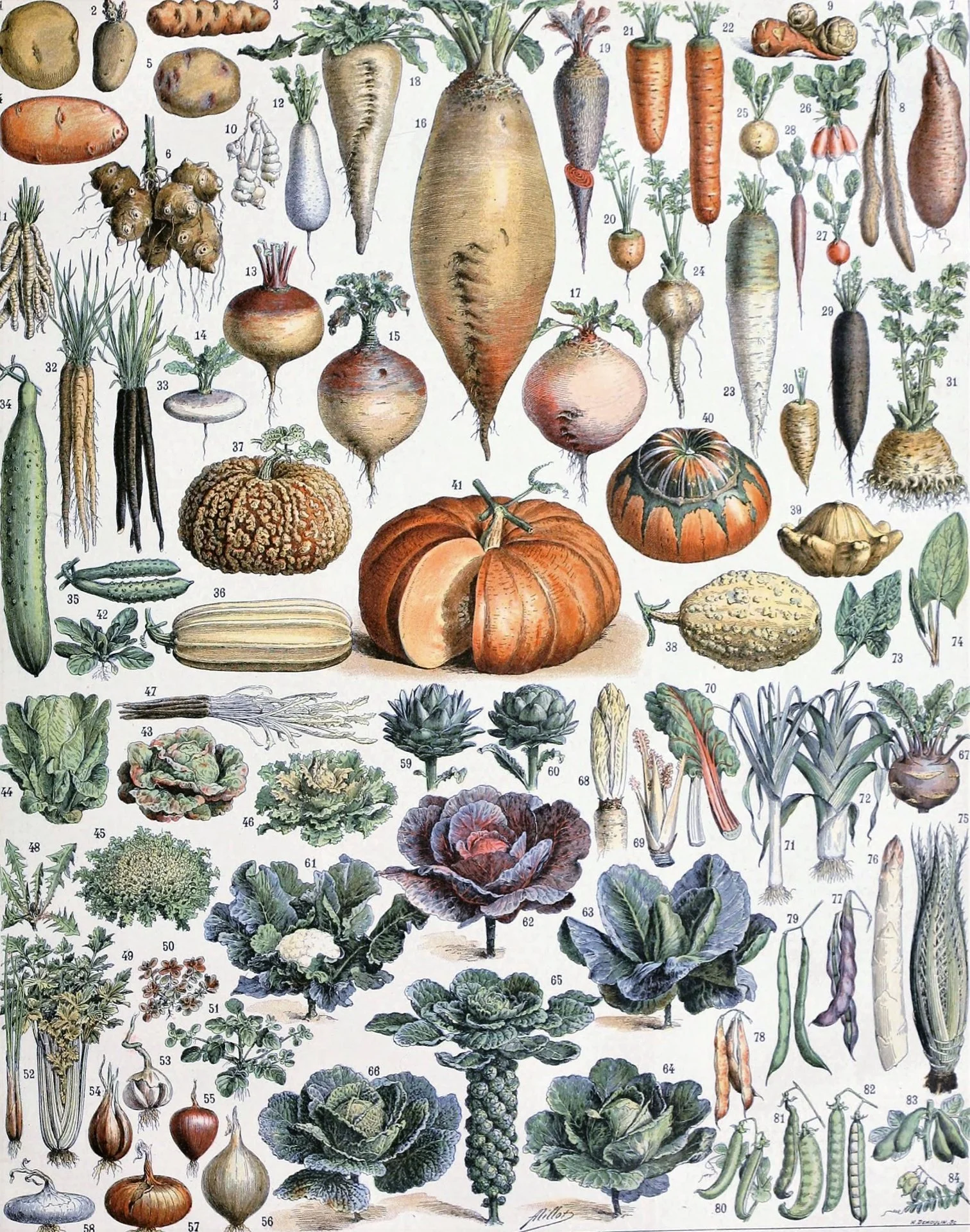

iii. Fish

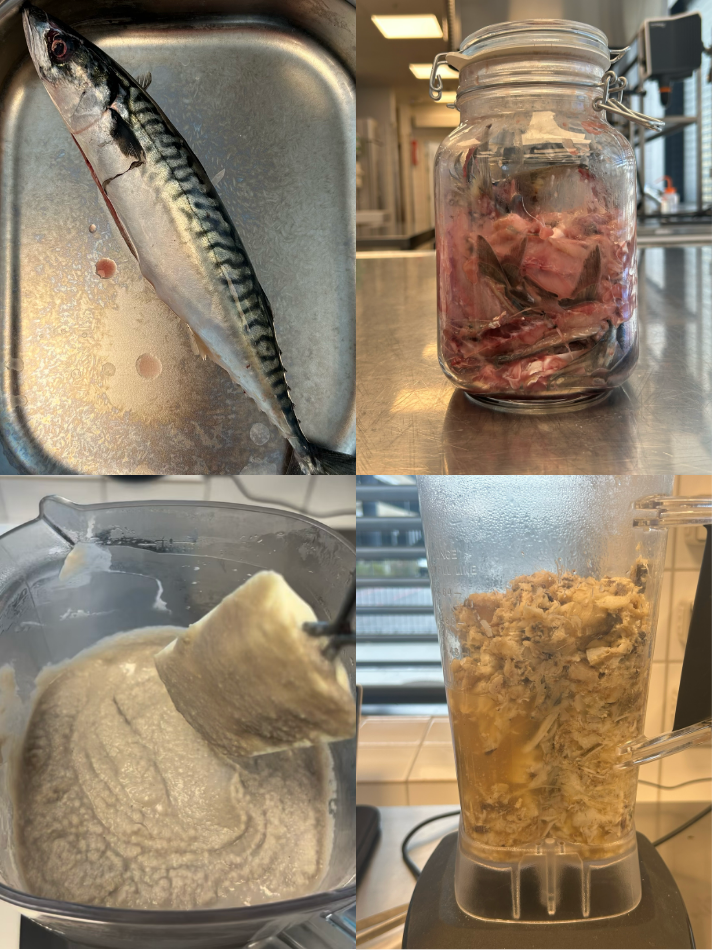

When butchering a fish, like a cod or a mackerel, the typical yield is usually less than 40% flesh. Most Western restaurants also usually only use the fillets, quite often discarding the rest of the carcass.³ But those bones, scales, offal and other bits are rich in nutrients like protein, fats and calcium. What if we could eat and enjoy them, too?

For some years now, I have been working on a process to liquify fish carcasses and transform them into a smooth paste with a clean taste of the same fish they come from that can be used as a versatile ingredient.⁴ This process can be done in a restaurant or on an industrial scale.

Making fish carcass paste

Recently, I have been experimenting with making different traditional fish dishes using this upcycled fish carcass paste, rather than whole fish fillets—for example, fiskefrikadeller. These are immensely popular and culturally important in our home base of Denmark. They are a type of fishcake that is usually eaten as a snack, quick dinner or an easy way to get children to eat fish. As a result, Danes have strong opinions about them.

Classic fiskefrikadeller, Københavns Kommune BørneMenuen

In a preliminary consumer taste test, my student Leo and I made fiskefrikadeller with different proportions of fish fillet and carcass paste, without otherwise altering the recipe. The most popular choice was a fiskefrikadelle made with 25% carcass paste and 75% fillet, outperforming even the 100% fillet version. The 50:50 version was also received positively. These early-stage results suggest that with further refinement, even more carcass could be included in the recipe and still be accepted and even preferred.

Taste-testing upcycled fiskefrikadeller

Like the bread burger, these fiskefrikadeller are another ideal use case for upcycling: why use whole fish fillets when they become not only unrecognisable because they just get blended up anyway, but when including the carcass actually makes the frikadeller a better product?

This fish carcass paste is high in protein, which gives it useful setting and coagulating functional properties, in addition to its nutritional value. Surprisingly, it doesn’t taste all that much of fish, especially when cooked in a final product. It can be used as an ingredient in all sorts of applications, like mousses, fillings and pastries. Upcycling can also be elevated, too, like this dish I made of carrots baked in cod bone pastry with globe artichokes and wild garlic.

Carrots baked in cod bone pastry with artichokes and wild garlic

By making this fish carcass paste, a chef can easily more than double the yield of ingredients that they typically get from the same fish. Twice the amount of food, and more delicious and nourishing food, without buying any extra. What else could we do if we apply the same logic elsewhere?

Sustainability doesn’t have to be about sacrifice; it’s about making the most of what you do have and enriching food culture through innovations that build on traditions.

iv. Coffee

Globally, nearly 10 billion kilograms of coffee beans are grown each year. Yet on average, less than 1% of the coffee in your cup is coffee bean.⁵ So, when we say we drink a lot of coffee, we do, but we also don’t.

Sometimes it doesn’t take much to transform something from inedible to a versatile, delicious ingredient. By simply milling spent coffee grounds for 24 hours with just-boiled water, spent coffee grounds are turned into a perfectly smooth paste that can then be used in all sorts of applications. I’ve used it to make miso, shōyu, a fernet branca-like spirit, ice cream, various baked goods and other treats.

For this talk, I developed a product inspired by Japanese yubeshi, which I first encountered at a teahouse during my time living in Japan. Traditionally, this is a sweet or savoury treat made by stuffing yuzu (a Japanese citrus fruit) with a mixture of miso and sticky rice flour and ageing it for up to a year. It’s then sliced thinly and eaten as a snack, or added to soups or salads. Here, the recipe uses juiced lemon halves and spent coffee miso to show the potential for high-end value from current waste streams. Find the recipe here.

Coffee miso lemon yubeshi

In Japan, yuzu yubeshi can be either savoury, when made with a filling of red and hatchō miso, or sweet, when filled with lighter misos, extra sugar and rice flour. While our coffee miso is dark in colour, it is also not fermented for very long, so it can be used in sweet or savoury applications.

Sustainability doesn’t have to be about sacrifice; it’s about gaining new ingredients and flavours without the need to produce or buy more food.

v. Conclusion

Sustainability need not be about sacrifice. It presents many opportunities for chefs: to gain new ingredients and flavours without the need to produce or buy more food; to redefine food traditions whilst respecting their heritage; and to have a say in food system transformation and bring about the future they want to live in.

Chefs are uniquely positioned to lead this shift by acting as cultural leaders, innovators and advocates for systemic change. A flavour-driven approach to sustainability ensures we can have rich, cultural and pleasurable food experiences today—and still have them tomorrow.

Contributions & acknowledgements

Kim developed and delivered the original presentation, conducted all the culinary R&D featured within it and documented it with photography. Eliot and Kim worked together to develop this article based on Kim’s materials, with editorial input from Josh.

Endnotes

[1] Which goes to show that upcycling is nothing new and the novel forms emerging today are just continuing a much older story of making the most of what we have.

[2] We haven’t done a Life Cycle Assessment for this, but since bread has much lower impacts across the board than beef (in general) and this burger is primarily made of a by-product of a by-product, it’s likely to be substantially less however you allocate the impacts. While in general we caution against carbon tunnel vision, whether you consider only greenhouse gas emissions or a more holistic set of sustainability metrics, using waste bread is probably ‘better’ than industrial feedlot beef. We also are not suggesting that we must make burgers for bread on a commercial scale. Ideally, there should never be enough bread waste to do something commercially. In the meantime, we think it’s a pretty nice proof-of-concept on the power of culinary upcycling.

[3] In many other cultures, and indeed in some Western restaurants, much more of the fish is often used.

[4] Even in cultures where much more of the fish is often used, eating bones is still not widely practiced.

[5] kaffebueno.com