The Spirits of Asilomar

Asilomar, a Spanish conjunction meaning ‘refuge by the sea’, is a state park in Pacific Grove, California, just south of Monterey Bay. Nestled among the dunes and coastal woodlands are the scattered timbered buildings of one of the more idyllic conference centres one can find. It was here, just over fifty years ago in 1975, that leading scientists working in genetic engineering came together for a conference, monumental then and since, to define what we might now call the safe operating space for their then-nascent field.

Asilomar, as the conference and its aftermath became metonymically known, has a complex and contested history. Some championed it as a laudable precedent of scientists taking responsibility for their science into their own hands. Others critiqued it as a gross overstep of elites preempting public and government oversight by making their own rules behind closed doors. Still others were ambivalent. Debates around Asilomar’s validity and legacy continue, with implications for broader conversations and policies about the relationship between science and society, the ethics of scientific research, and how publics should be involved in setting research agendas and policies.

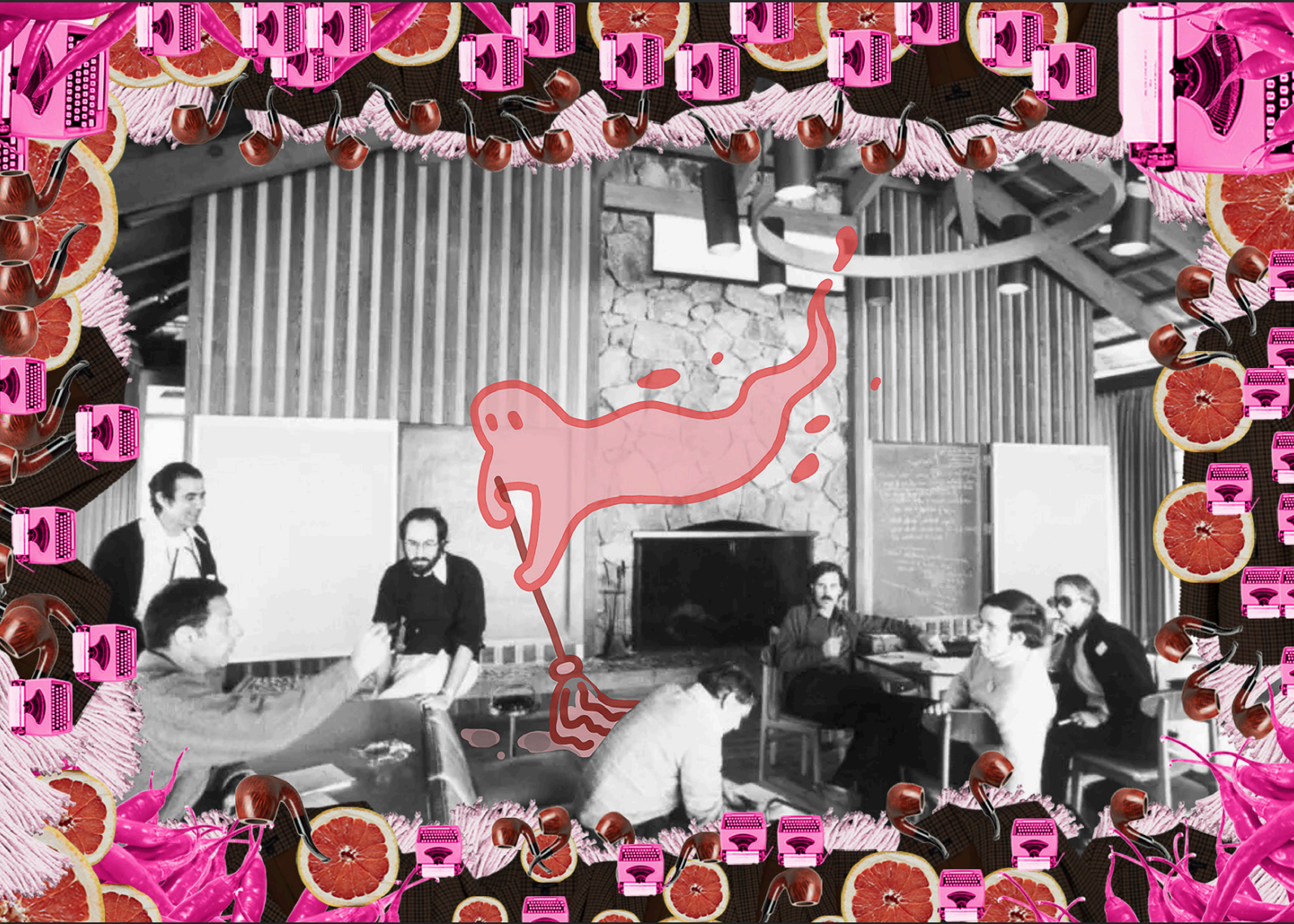

One thing that most participants in that 1975 conference seemed to agree on was that it had what many called a special ‘spirit’. ‘The spirit of Asilomar’, characterised by its relatively open-ended, deliberative nature untypical of most scientific gatherings, became part of the conference’s mythology and legacy.

Earlier this year, over the original’s same dates in February, another Asilomar conference was held. ‘The Spirit of Asilomar and the Future of Biotechnology’ was organised, as its website says, not only ‘to reconvene and look towards the future’ but ‘to grapple with the past – aware of its accomplishments, limitations, and failures – so as to better engage with the issues of the present.’ It presented an opportunity to gather—not only scientists this time but also social scientists, policymakers, entrepreneurs, artists, members of civil society, and a cohort of next-generation leaders—to consider how synthetic biology might and should proceed from here.

I first learned about Asilomar, its history and current invocations, from my colleague Erika Szymanski, a fellow STS scholar who works on metaphors as scientific tools, particularly in synthetic biology. On a visit to Copenhagen in autumn of 2023, Erika told me about Asilomar, and how the phrase ‘the spirit of Asilomar’ always makes her think of actual distilled spirits—prompting her to wonder what, if anything, the ‘spirit of Asilomar’ would smell and taste like. This of course I found captivating, engaging as it did shared interests in the underappreciated role of specific places to the process and practice of science, the role of the historically maligned ‘proximal’ senses in the production of scientific knowledge, and smell and taste and modes of chemical communication within and across species.

So, the following summer, when Erika wrote asking if I’d like to collaborate on making this sense-able ‘spirit of Asilomar’ a reality, to serve to the conference’s 300+ participants and hopefully invite reflections on these questions of sensory knowledges, placefulness, and multispecies agencies in science, I had to say yes. How, we wondered, by ‘beveragising’ the spirit of Asilomar, might we invite reflections and encourage conversations on the past, present, and future of synthetic biology that might not happen otherwise?

At first, we set out to make one distilled spirit, incorporating flavour notes that could speak to all of these themes. That quickly became gastronomically unwieldy, and logistically complicated. Not to mention conceptually unsatisfactory—it became clear to us that the history and legacy of Asilomar couldn’t properly be contained by one single, internally consistent spirit, and that trying to would run counter to the messy, contested nature of its diverse histories.

We realised it made more sense, both conceptually and practically, to instead develop a small menu of different cocktails, each of which could speak more clearly to a different theme and be more gastronomically coherent (and thus hopefully also enjoyable). Drawing on archival materials from the original conference and our own research interests, we developed three cocktails each addressing a key theme in these entangled histories—one for placefulness, one for multispecies action, and one for participatory inclusiveness—to open important conversations and suggest alternative trajectories for the future. We started by identifying key flavour notes that would speak to each theme, then finding a classic cocktail that could accommodate the flavours best and be made with minimal additional on-site prep and training.

We also offered a simpler drink—‘just a beer, thanks’—for those who couldn’t be bothered with all the spiritual talk and just wanted some raw material for unwinding after a long conference day. All the beverage options we also offered in non-alcoholic or trace-alcoholic form. And finally, as we were sure there would be many more than three potential spirits of Asilomar, we also offered conference participants an opportunity to propose their own.

We share the concept, photo, and recipe for each drink below.

The Placeful Spirit

Geographic G&T

The world of synthetic biology seems generally to be premised on decoupling: of microbes from their contexts, of society from ecology. A key part of this decoupling is the universalising aspirations of the laboratory, as many STS scholars have shown is central to many laboratory sciences, and indeed the very concept of the laboratory itself. What might happen to and for synthetic biology if we try to re-root its practices in specific places, and/or allow it to acknowledge how place-based its knowledge practices already are? And how might the visceral sensory modalities of taste and smell, the latter in particular being so tied to memory, be particularly well-suited to this task?

For this cocktail, we started with key features of the Asilomar site itself: the Pacific ocean, and the distinctive Monterey pines that used to dominate the landscape but were wiped out by a fungal disease from the 1990s—present at the original Asilomar conference, now a ghost. To evoke the sea, we played around with distilling different seaweeds; for the pine, not able to get Monterey pine itself, we opted for Giant pine (Abies grandis), which has similar sensory characteristics. For the seaweed we ended up going for dulse (Palmaria palmata)—others became muddy and unpleasant, while dulse, when distilled under vacuum, expressed its floral and tea-like notes while retaining a clean oceanic depth. For such delicate botanical flavours, we wanted a clean, simple cocktail that could let these two additional flavours shine. A classic G&T was the one.

We wanted to use a garnish of ice plant: it was planted by conservationists in the latter half of the 20th century to protect the dunes from erosion, then torn up again by conservationists in the early 21st century to restore native dune habitats. And its glistening texture and slaking crunch, we thought, would have been a perfect complement and visual pop to the otherwise somewhat austere drink. It proved outside our budget, but in our minds the thought lives on!

Recipe

a) Dulse Extract

Method

Cover the dulse with the ethanol and soak overnight at room temperature.

Add the water and distil in a Rotovap at 45˚C, 30 millibar.

Store sealed, in a cool and dark place.

Ingredients

6g dried dulse

100g ethanol 99.9%

140g water

(b) Giant Pine Extract

Method

Cover the pine with the ethanol and soak overnight at room temperature.

Add the water and distil in a Rotovap at 60˚C, 40 millibar.

Store sealed, in a cool and dark place.

Ingredients

100g giant pine needles

100g ethanol (99.9%)

140g water

(c) Geographic G&T

Method

Pour all into a highball glass over ice and stir.

Ingredients

30ml Tanqueray No. 10 Gin

4.36ml (4g) dulse extract (a)

4.36ml (4g) giant pine extract (b)

90ml Fever Tree Mediterranean Tonic

(d) Non-Alcoholic Version

Method

Pour all into a highball glass over ice and stir.

Ingredients

120ml Fever Tree Mediterranean Tonic

4.36ml (4g) dulse extract (a)

4.36ml (4g) giant pine extract (b)

The More-than-Human Spirit

Multispecies Manhattan

In agriculture and food production, often the products that are the most distinctive, intense, and/or complex in flavour, and thus gastronomically valued, seem to be those where the human producers see their role as one of guiding and supporting the agencies of the nonhumans involved, be they animals, plants, and/or microbes, rather than trying to dominate or control them. If we can understand flavour as a ubiquitous mode of communication within and across species, this observation makes sense—the distinctiveness, intensity and/or complexity of flavour is a result of more opportunities for more voices to join the chemical conversation, and/or articulate themselves more fully. So similarly we might ask: what could happen to and for synthetic biology if we try to allow for nonhumans, in this case model microbes, to speak more and speak back? And how might the medium of alcohol, as an excellent solvent of flavour, help record, clarify and amplify these nonhuman voices?

Here we started by thinking about some of the distinctive aromas of microbiology labs that might also work in a cocktail: malt agar medium, yeast, geosmin (from Pseudomonas). We also thought about some notable metabolites already produced industrially by microbes, like vanillin (by engineered yeast) and citrate (by Aspergillus niger), as well as key aspects of lab practice and infrastructure, like latex gloves. Glutamate, of course, is both a common component of media and a common metabolite, and the source of umami taste—so we knew we had to get that in somehow. This drink we could have taken in a lot of different directions; but we ended up being most taken by the combination of malt, yeast, and vanilla notes, both conceptually and gastronomically. This triad took us into dark cocktail territory—some kind of American whiskey-based drink to bring in the malty and vanilla notes. Having landed on whiskey as the key spirit and with these dark, rich notes in mind, we went with a loosely Manhattan-based grammar, centred around Bourbon. Instead of vermouth we made our own mixture of malt extract, yeast extract, and citric acid to bring the requisite sweetness and touch of acidity, as well as our own surprise umami edge. Kim brought in some honey for balance, as only using malt extract for sweetness felt too heavy. For the bitters, part of the classic drink, we used a lemon one, to tie in with the citric acid and to add some more refreshing top notes. Finally we found we needed a dash of water to let all the dense, intense flavours down a bit, to give them room to breathe and mingle.

The non-alcoholic version uses a rooibos and black pepper infusion instead of whiskey.

Recipe

a) Multispecies Manhattan

Ingredients

50ml Maker’s Mark Bourbon

12g Mangrove Jack’s light malt extract

12g honey

1.4g Marmite

0.25g citric acid

1.7g Bitter Truth lemon bitters

20g water

Method

Stir everything except the bourbon until well incorporated.

Add the bourbon and shake in a cocktail shaker over ice for 10 seconds.¹

Strain into a rocks glass over ice.

(b) Vanilla Rooibos and Black Pepper Tea

Method

Bring the water to a boil.

Add the tea and pepper and steep covered for 5 minutes.

Strain through a mesh sieve and cool to room temperature before using.

Ingredients

250ml water

4g Vanilla Rooibos tea leaf

(Tante T)

0.5g cracked black pepper

(c) Non-Alcoholic Version

Method

Stir everything except the tea until well incorporated.

Add the tea and shake in a cocktail shaker over ice for 10 seconds.

Strain into a rocks glass over ice.

Ingredients

60ml Vanilla Rooibos and black pepper tea (b)

12g Mangrove Jack’s light malt extract

12g honey

1.4g Marmite

0.25g citric acid

1.7g Bitter Truth lemon bitters

20g water

The Human Spirit

Participatory Paloma

The 1975 conference participants were, as might be expected, largely white male natural scientists in senior academic positions. Many more voices with a stake in the matter, as the critical aftermath of the conference showed, would probably have been relevant to include. Similarly, many more people were part of making the gathering possible—the cooking, cleaning, and management staff of the park and conference center; the wives left at home to care for children; the research assistants supporting the scientists on site and keeping laboratories running in their absence—but are largely left out of the story, or don’t even appear in the archive to make their presence in the story possible. How might we reimagine a synthetic biology, and a science in general, that is better at acknowledging, valuing, and integrating the concerns of these vital groups? How would doing so require new sociotechnical modes of organisation, and how might it invite us to do science differently?

In some ways this one was, at least at the start, the hardest drink to figure out. Unlike with the G&T and Manhattan, the concept was a bit more abstract, so it didn’t immediately suggest concrete substances we could use as ingredients. This quality forced us to think a bit more laterally. We talked a lot about how we could somehow include ‘the masculine’, but without uncritically reproducing stereotypes and clichés that serve no one. Instead we turned to the archive of the original event to look at actual participants and see if we could find some clues. Many of the men wore wool sweaters or blazers, and multiple photos depict them passionately conversing in a variety of casual settings and postures. We know from the textual archive that the days were long, the discussions were often heated, and the sense of urgency high. What, we wondered, might these gatherings have smelled like to be in? Probably, we imagined, a complex mixture of different sweats, making their woollen clothing fragrant. Some of the men are also depicted smoking pipes; we wondered if we could bring in tobacco, or smoke. And on a more metaphorical level, we brainstormed how we could bring in the sense of tension, of conflict, of spirited discussion—maybe with some saltiness, some bitterness, some spice. Suddenly things started to congeal: a Paloma could fit the bill, with some tweaks. The tequila would give us a funky, slightly rank base, to help conjure the musk of exertion; the grapefruit soda would bring a welcome bitterness. For the wool we made a distillate of lanolin, the fat of wool, which brought a surprising delicacy and slightly waxy texture. We finished it off with a chilli salt rim, using smoked salt, to bring in the salty ripostes, the spicy rebuttals, and the smoky haze.

Recipe

a) Lanolin Extract

Method

Cover the lanolin with the ethanol and soak overnight at 60˚C (e.g. in a waterbath).

Add the water and distil in a Rotovap at 60˚C, 40 millibar.

Store sealed, in a cool and dark place.

Ingredients

100g pure lanolin

100g ethanol (99.9%)

140g water

(b) Chilli Salt

Method

Grind both ingredients together in a spice grinder until fine enough to rim the glass.

Store in an airtight container until use.

Ingredients

50g smoked sea salt

5g dried ancho chilli

(c) Participatory Paloma

Method

Rim a Collins glass with the chilli salt.

Pour all the liquid ingredients into the glass over ice and stir.

Ingredients

60ml Don Julio Blanco

4.36ml (4g) lanolin extract (a)

15ml lime juice

120ml Fever Tree Sparkling Pink Grapefruit

Smoked chili salt (b)

(d) Non-Alcoholic Version

Method

Rim a Collins glass with the chilli salt.

Pour all the liquid ingredients into the glass over ice and stir.

Ingredients

180ml Fever Tree Sparkling Pink Grapefruit

4.36ml (4g) lanolin extract (a)

15ml lime juice

180ml Fever Tree Sparkling

Pink Grapefruit

Smoked chilli salt (b)

The Non-Spirit

Just a beer, thanks

Some people might not have been interested in the creative encounter at all, but we still wanted to give them a way to join the cocktail hour as part of the conference’s programme. Thus, beer. While we didn’t end up needing a card for this drink, if we had it would have read:

“There is no Spirit of Asilomar, and whatever supposed spirit might exist is a fiction invented by sensationalist journalists who just want a good story to tell. That spirit should be killed and forgotten because it gets in the way of getting the work done. The Non-Spirit of Asilomar is the no-nonsense scent of getting on with it, grabbing a sandwich mid-meeting, focusing on the science and not faffing around worrying about context. Just a beer, thanks.”

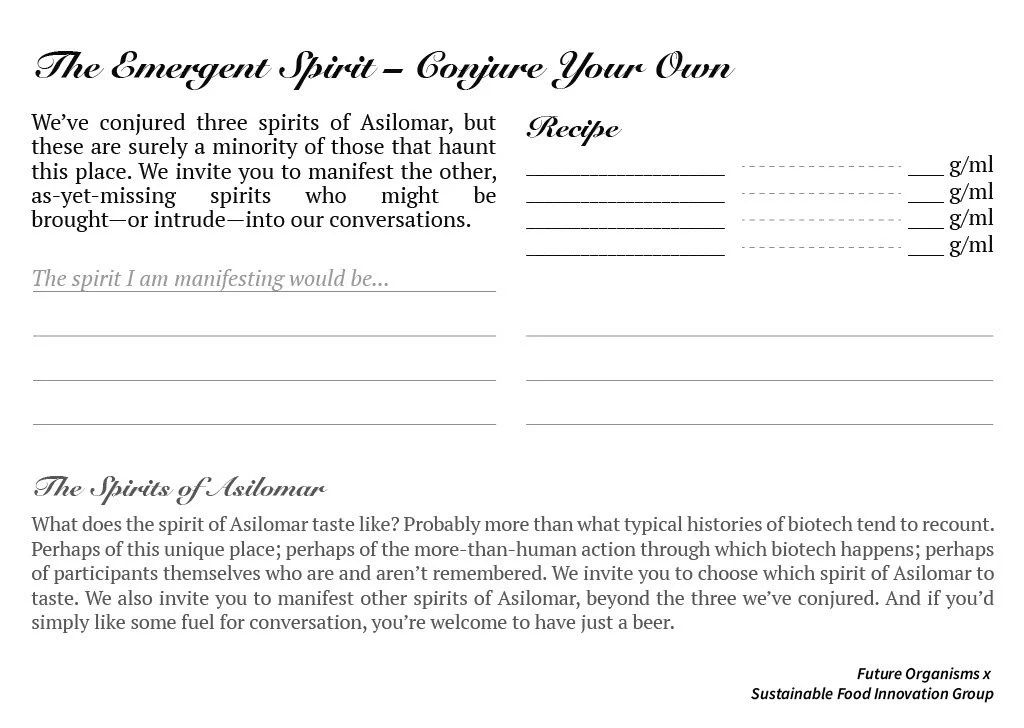

The Emergent Spirit

Conjure your own

Especially given the participatory aspiration that suffuses the spirit of Asilomar and which we wanted to encourage, it would have seemed wrong for us to definitively and exhaustively say what the three spirits of Asilomar should be. So we made an option for participants to ‘conjure their own’, at a station where they could draw and describe their spirit and come up with a recipe by which they could beveragise it.

Contributions & acknowledgements

Putting this project together wasn’t easy—even just the logistics of trying to make a bespoke cocktail service at a site neither Erika nor I had been to before were not the most straightforward. But we were grateful for the chance to contribute this offering alongside a programme of other artistic and creative ‘activations’ the conference organisers curated—which for me was one of the best and most engaging parts of the conference experience. Offering people unexpected spaces to think and meet each other in, and surprising, multisensory experiences to engage with together, can break the ice, ease the inevitable alienations of such interdisciplinary and intercultural gatherings, and prompt thoughts and conversations that might not otherwise happen. This was the spirit in which we sought to ‘beveragise’ the spirit of Asilomar—not for mere commemoration or celebration, but to invite engagement with its complexity and to enable alternative trajectories for biotechnology.

Our thanks to the many people who made it possible.

Credits:

Concept creation & development: Erika Szymanski & Josh Evans

Cocktail conceptualisation: Erika Szymanski & Josh Evans

Cocktail recipe development: Kim Wejendorp & Josh Evans

Cocktail photography: Eliot Beeby, Kim Wejendorp, Taylor Rayne & Nurdin Topham

Visual design development: Erika Szymanski, Josh Evans & Yuning Chen

Visual design execution: Yuning Chen

Illustrations: Theo Altmaier & Hazel Shelton

Text: Erika Szymanski & Josh Evans

Service execution: Raymond Jocson, Edwin Garcia, and the rest of the Asilomar Conference Center staff

Project management & production: Erika Szymanski & Josh Evans

Project support: Luis Campos, Jane Calvert

Funding: ‘Future Organisms’ (UKRI x NSF), ‘Sustainable Food Innovation Group’ (NNF)

Endnotes

[1] We know a Manhattan is typically stirred, and not shaken; but in this case, a quick shake benefited the drink immensely, lightening up an otherwise dark, heavy, and rich mixture (heavier than a classic Manhattan), making the full range of flavours more discernible, and improving the balance and drinkability.