Sensing Holobiont

Welcome hungry holobionts

Assemblages of microbial and human cells

Micro and macro oddkin: Odd in size, kin in cometabolism

Let your billion mouths body absorb this world

of symbiotic becomings, taste its potential

and digest it into new and tender

recipes for reciprocity.

Smelling, tasting, and eating can feel like some of our most personal, intimate acts. My body, my tongue, my gut, my experience, my feelings. What happens when we realise we never eat on our own, but always with and for and thanks to other species, on and in and all around us? And how might this realisation in turn shape how we eat, sense, and orient ourselves to all our earthly companions?

These questions guided our collaborative creation of an art–science public engagement project called ‘Sensing Holobiont: flavourful rituals for metabolic companions’. Through immersive, multisensory experiences and flavourful storytelling, we sought to explore how ‘holobiont thinking’ can contribute to sustainability, ecological regeneration, and planetary consciousness.

We joined this story in May 2022. A colleague—Joana Formosinho, then a PhD Fellow at the Medical Museion at the University of Copenhagen, doing research on the figure of the holobiont in the life sciences—reached out to me. She asked if we might want to be involved in ‘conjuring up a “holobiont dinner”’, likely involving fermented foods and some kind of meditation/playful experience for guests, inviting them to eat as holobionts. It would be led by artists Baum & Leahy, with whom Joana had already collaborated on a piece called ‘Co-metabolise’ for the Museion’s exhibition at Kunsthal Charlottenborg called The World Is In You in 2021-2022, and curated by Louise Whiteley, associate professor and curator at the Medical Museion and one of Joana’s supervisors. Louise also worked on Co-metabolise, along with Rob Dunn, professor of ecology whose lab has been doing some super interesting studies of the ecology, evolution, and biodiversity of fermented foods. The project would celebrate the end of ‘Microbes on the Mind’, a Velux-funded grant led by Louise, and would coincide with a three-day workshop gathering of the Nordic Network for the Social Study of Microbes, led by Salla Sariola at the University of Helsinki. They hoped the work would reach these different audiences—researchers studying microbes, food, and food systems across disciplines, artists thinking and working with microbes, food producers and fermenters, and other interested publics.

I had done a bit of work with the Medical Museion before, whose wonderful exhibitions on the history and culture of medical science and whose experimental approach to public engagement I’ve always found captivating. So the opportunity to play more together, especially with such an enticing group of collaborators, was the easiest thing to say yes to. They needed a partner who could help develop and lead the food side of things. We were happy to do it.

From summer we met and began fleshing out ideas and plans—Rose (Leahy), Amanda (Baum), Louise, Joana, Rob, Kim and I. Together we pooled ideas, conceptualised the piece and what it should explore, and brainstormed its tone and style. Rose, Amanda, Kim and I took the lead on developing the structure and content of the work; the installation, menu, and performance were so interlinked and had to be developed together. Once we had worked out some menu ideas, Kim worked intently on recipe R&D throughout the fall, holding tastings and iterating the dishes in feedback with Rose and Amanda’s evolving artistic vision. At critical points in the process we shared our progress with and sought feedback from the others (Louise, Joana, and Rob). Together, we wrote the script and descriptive text, planned all the complex logistics, installed and prepped everything, and rehearsed. Somehow, with a lot of work from all sides, including a host of supporting hands from Museion, Baum & Leahy’s network, our group, and assorted friends and colleagues, we pulled something together in time for the performances, from 9th to 11th of January, 2023.

Sensing Holobiont: Flavourful Rituals for Metabolic Companions (2023)

Combining novel gastronomy, interactive installation and microbiome research, Sensing Holobiont explores the vital connections among species, bodies, food and the environment. Taking cues from the growing movement in the sciences to recast multicellular organisms as ‘holobionts’ the work asks: How might a multisensorial ceremony help us to recognise and realise our holobiont selves? And how might this realisation change our relationship to our bodies, to eating, and to planetary health?

A holobiont is an ecological unit consisting of a ‘host organism’ – animal, plant or fungi – and the associated microbes, viruses and smaller holobionts living in and on it. While implications of the ecological, evolutionary and daily dynamics of holobionts are being increasingly studied, Sensing Holobiont invites us into a shared exploration of the flavourful complexities of being multispecies consortia.

While it’s not possible to reproduce the work in full here, I’ll try to offer a little taste of the project and a tour through its arc:

You arrive at the Medical Museion in the center of Copenhagen, housed in the original late-18th-century buildings that used to house the Royal Academy of Surgeons. Outside it is dark, just before 6 o’clock in the evening; the museum is closed for the day. A guide opens the heavy wooden front door and leads you through a warren of narrow, crooked corridors, up and down, eventually ushering you into a small candlelit room. A host welcomes you, invites you to put down your bag and hang your coat, and offers you a glass of something bubbly, aromatic, a bit herbaceous, slightly cloudy. The bubbliness awakens your senses; the light alcohol (if you’ve chosen wine over kombucha) calms your nerves after the workday. An excited murmuring grows as your fellow guests arrive.

Once your group, just under thirty, has assembled, a host addresses you, a group of symbiotic metabolic companions. When you enter the space, the guide tells you, you will encounter a series of flavourful encounters. In each, there will be a short incantation and something to taste. You will be invited to activate the encounter together by each reciting one line of the incantation. Your guide will offer you a taste of that encounter, share its story with you, and invite you to explore different dimensions of being a holobiont, through reflection, discussion, and play.

After each encounter, you will be guided to the next. There will be a bit of time in between encounters where you are welcome to get to know your group, share your experiences, and digest together.

‘We hope you will enjoy sensing yourselves as holobionts.’

The host then ushers you, and eight of your fellow guests, through a door, into the first room.

A mound of earth, heaped upon and surrounding a low table, is circled by cushions, filling the middle of the small anteroom, dark and lit by violet. An atmospheric, textured soundscape suffuses the space, intensifying the dank, rich smell of soil. The guide invites you to join them around the earth table. The guide picks up a textured linen cloth, and begins rinsing their hands with it. With a gesture, they invite you to do the same. The intense soily aroma seems to emanate from the cloth, though it is clean and lightly steaming. The guide puts down their cloth. You follow. They lift their hands to their face and inhale deeply. You do the same—and are enveloped in a humic cloud.

The guide leads you through a brief meditative ritual around soil and geosmin, the scent of earth, a vast microbiome from which many others emerge, and with which we are in intimate evolutionary relation—a vivid example of which is found in Mycobacterium vaccae, a bacterium that lives in soil and, when it comes in contact with our bodies, stimulates the production of serotonin.

Geosmin, soil, earth, dirty life-support

Interface for the interlace

Of matter, minerals, gases, liquids, organisms

Home to vegetal holobiont unfoldings

Plant, fungal, composting companions

Unearthing emotions, memories, fermenting new directions

Replenishing contaminated landscapes

Cities, forests, holobiont bodies

‘When you are ready, open your eyes, and progress to the next room.’

You and your group open out into a larger room—long, with different sizes and shapes of wavy tables in orange hues, lit at angles with soft reds and purples. A serene soundscape fills the space with overlapping organic tones of bubbling, squeaking, slithering, and creaking.

A new guide beckons you to a tall nearby table, festooned with what looks like yellow wool. On it are small yellow hemispherical cups. The guide pours a bubbly liquid into each cup, and invites you all in a collective toast. You take a cup and hold it to your lips. Fruity, floral aromas and tiny, tangy bubbles dance on your upper lip. A pleasant herbal woodiness hangs in the background. The cup itself, you notice, is made of beeswax, with its heady fragrance. A spherical ice cube bumps against the cup’s edge; as it melts, petals within it unfurl.

The guide describes this as a spontaneous kombucha—not made from an existing kombucha, as is usually done, but assembled by mixing microbes from honeybees, sunflowers, and human skin in sweetened tea, and letting a SCOBY emerge.

Sunflowers, honey bees, and humans collide

Plant, insect, mammal microbiomes co-mingle

In honey-sweetened tea, new niches emerge

Pellicles erupt at a petal’s edge

Growing into a thick mat, firm and soft symbiotic culture

When the right bacteria and yeasts meet

Mothers happen, over and over, all the time

Some mothers have mothers, and some mothers don’t

Parentless, lineage-defying cellulosic homes

For sweet and sour spontaneous assemblies

From here, the guide directs you to a large glass sphere in the center of the room. Another guide welcomes you with an invitation that it’s now time to exchange microbiomes. The glass sphere is filled with a large amount of what looks like dough. The guide lifts a lid, revealing a hole. They dip their arm into the glass up to their elbow, pull out a small clump of dough, and begin to knead it, inviting you to do the same. As you all are kneading your dough, the guide explains that this is sourdough starter, and by kneading it, you are offering your microbes to the starter, and gaining some of the starter’s microbes in return—a millennia-old process of exchange. The guide then invites you to return your kneaded ball to the glass sphere, where it will become part of a collective sourdough starter.

The guide then ushers you to a low table surrounded by wavy stools and cushions stuffed with straw. The table is set with what look like different forms of dough, now baked. The guide explains that the bread, served on salt-dough platters, has been baked using the collective starter from last night’s guests; and the collective starter your group just contributed to will be used to bake the bread for tomorrow night’s guests. There are platters of rouille, an emulsion made from yesterday’s bread and oil, dusted with carrot powder, to swipe today’s bread through. Before digging in, you are invited to recite an incantation for this ongoing cycle of hands, microbes, and nourishment, carved into salt dough ornaments placed around the table.

We cometabolise

We share digestion

We eat one another

We eat for each other

We, a whole life of many

We, commensal messmates

We share guts

We share a table

We, symbiosis

After lingering a while, breaking and sharing bread with your hands and exchanging impressions with your fellow guests, you are invited to the next encounter. You gather around a table covered with what looks like translucent, speckled leather, scattered with small brown cups covered in the same material.

The guide points to a large spiral at the center of the table, underneath the leathery covering, with what appears to be a series of element names and large numbers. This is the human stoichiometric equation, they tell you: all of the elements that go into making a human body. But something important is missing from this classic equation—all the elements that make up our symbiotic microbes. The guide offers you a wooden stylus and small cups of a deep teal pigment—ink made from spirulina. They invite you to help rewrite our human stoichiometric equation by tracing microbial runes lying underneath the algal leather with the ink, contributing to a collective holobiont tapestry that will accumulate runes over the run of the work.

These microbes, your guide describes, especially in the gut, thrive on prebiotics—foods high in fibre, and sugars and starches otherwise difficult for our body to digest. Which is the theme of your next tasting. The guide invites you to pick up one of the small brown cups lidded in soft, smooth, slightly tacky algal leather, and to hold it as you recite the incantation, winding through the card intestines hanging along the wall.

Eat information, bodies in formation

Read and rewrite your cells, your selves

By the genes of our metabolic companions

Seaweeds, vegetables, fermented grains

Biotic matters, pre and pro, to sustain all of you

Atomic alphabets, sour signals, lacto language

Building immunity from multiplicity

In cellular text we sense, name and know

The holobiont’s microglyphs

The tasting, your guide tells you, is built around pre- and probiotics—ingredients that both feed the gut microbiomes and contribute new ones. You lift the squishy lid of your bamboo cup. Inside is a small pile of different grains and legumes, a mixture of barley, buckwheat, black lentil, flax seed, and red rice. These grains have been fermented into nattō—a sticky, slimy, pungent Japanese condiment, typically made with soybeans, using the bacterium Bacillus subtilis var. natto.

Your guide takes a wisp-thin piece of rice paper from the table, places it on top of the open cup, and puts the lid back on. You follow suit. They pick up the cup, flip it over, and remove the cup, now on the top, revealing a deep purple pickle made with red cabbage, cucumber, aubergine, and seaweed, now sitting on top of the nattō, and a bit of freeze-cured egg yolk to bind everything together. You do the same. You pick up your rice paper natto wraps together and slide them into your mouths. The rice paper collapses into a momentarily sticky veil then dissolves, leaving a complex play of shapes, textures and flavours, echoing the runic forms across the leather tapestry.

A quiet settles over the group as you chew slowly. The whole grains, legumes, and vegetables, the guide offers, are rich in prebiotics; the nattō, as well as the lactic acid bacteria in the fermented cabbage and the acetic acid bacteria in the pickled cucumber, aubergine, and seaweed are rich in probiotics. The acids themselves, as well as the ginger in the pickle, are bioactive, shaping the composition of the gut microbiome community. And the rice RNA in the rice paper can even act on the human genes, turning them on and off. Eating doesn’t just provide raw material to nourish us and our gut microbes—it also carries information, sending signals that shape our body from the inside out.

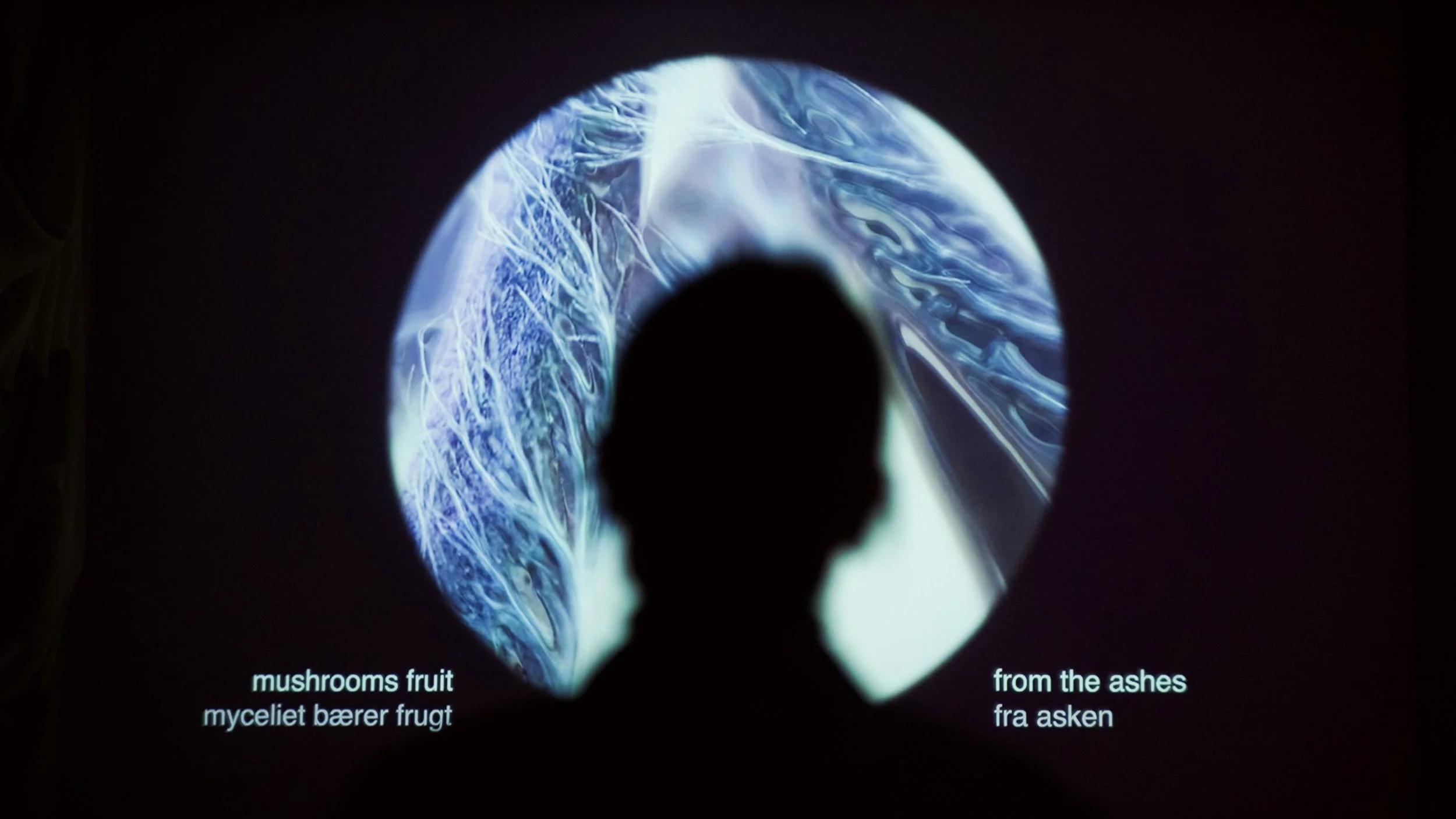

From here, the guide turns you loose to explore a blasted landscape, where you can forage on your own for your next taste. They do not tell you what it is, other than you’ll know it when you find it. You step into a corner of the room strewn with straw, blocks of mycelium with mushrooms sprouting from them, and branching sculptures of fluffy white. Cushions and woven straw seats beckon you to sit and lie, getting low to explore. A meditative video with the incantation loops above.

Your group first enters hesitantly, but spreads out and begins to feel at home. Together you begin to come across a series of curious objects—mottled, slightly elongated tuber-like bulbs, knobbly and dark brown, dusted with green and black.

You gingerly pick one up nestled among some mushrooms on one of the mycelium blocks. It fits in the palm of your hand, and is surprisingly heavy. You smell it—deep, foresty aromas, with an enticing savouriness. You tentatively take a bite. A crisp vegetal shell yields to your teeth which sink through to something soft, dense, and rich. Pleasing notes of mushroom fill your mouth and nose, cut through with a hint of fruity acidity. You take another bite, more confident this time, enjoying the moreish morsel with gusto. You look around you—your group are similarly enjoying their finds, some slightly bewildered, some entranced.

A guide passes, gently telling you what you’re tasting: a crispy shell of Jerusalem artichoke dusted with parsley and charcoal powders, filled with a morel mushroom mousse and pear gel.

For a few moments, your group lounges in the mycelial world, some softly chatting, others gazing up at the film as the incantation unfolds.

Holobionts are not just animals, but extend into and across the landscape, like mushroom mycelia with tree roots, fruiting after forest fires.

After relaxing in the straw, a guide collects you and brings you to the final encounter in the room—a table wrapped with translucent bendy tubes in different thicknesses, coiled around wide glass bowls filled with different coloured substances. Some of the tubes seem to be filled with what look like tiny seeds suspended in a pink gel.

The guide invites you to sit. Our gut microbes love to produce slime, they tell you, turning all those fibrous prebiotics into a mucosal layer that serves as habitat, buffering them from the environment and serving as a selective interface with the center of the gut and the intestinal wall. Slime is how our gut microbes both connect with and remain separate from our bodies and the outside inside our guts.

For dessert, you are invited to assemble a medley of flavourful slimes, to inhabit it as our gut microbes do. The guide shows you how to assemble your own dessert in a small glass bowl from the large bowls on the table: chia seeds jellied in caramelised honey, basil seeds slickened in raspberry purée, and guava gel, topped with a pool of jewel-green basil oil. You pick up a spoon with a twisted blown-glass handle and dig in, noticing how the different textures of slime and the oil mingle but do not mix, a separate togetherness echoing the mucosal membranes of our gut lining—a key holobiont matrix.

After you delight in the playful slime time, your guide draws your attention to an incantation, scrawled in segments on the thicker tube filled with pink.

Slimy seeds and fibrous fruits

Simultaneous ooze in spoon and gut

Deep inside the human body

In the multi folded bowel

Lined with moist, gelatinous mucus

Symbiotic space thick with delicious difference

Is a recipe for multispecies cell cohabitation

Mucus separates, mucus relates

Being holobiont is living well in structured slime

You are invited to help yourself to seconds, as much slime as you like, and to play with different proportions to your taste.

Once you are sated, your guide takes you all back into the anteroom where you began. Here, you recline together, listening to your own and each other’s guts with stethoscopes, connecting aurally to your microbial companions, listening in on the conversations happening with all the new signals shared throughout the different encounters, ecosystems recognising each other as ecosystems. Your guide invites you to reflect on what you experienced, to share how you felt, and if any of the encounters or rituals led you to relate differently to your body, your microbes, and/or each other.

After some final words, the guide leads you back out to the welcome room, where you leave some of your thoughts on a large poster, and take a menu from the evening.

The holobiont is a fascinating and important idea that is starting to revolutionise the life sciences. But it can be hard to fully grasp on an intuitive level what it means for how we might think about relationships between lifeforms and our own place in it all. Based on the many rich responses the project team received in the survey feedback after the work, it seems that bringing together art, science, and cooking, particularly through fermentation, can be a powerful way to make holobiont thinking more sense-able and intuitively understandable. This understanding, in turn, can transform how we see ourselves, and help link the health of our bodies to the health of the planet. That possibility is something we and the rest of the team hope to explore further in future iterations of the work.

For us in SFI, Sensing Holobiont was an exciting exercise in how we can use art to bring together disciplines and media, and explore new, delicious ways of cultivating sustainable consciousness. We were thrilled to be part of this brilliant team and contribute our gastronomic, theoretical, and creative expertise to the project.

Other institutions have been interested in hosting reproductions of the work, which is something we are keen to explore. If you would like to work with us to mount a version of Sensing Holobiont, and have funds and institutional support to enable it, you are most welcome to reach out.

Acknowledgements & contributions

Concept development: Amanda Baum, Rose Leahy, Josh Evans, Kim Wejendorp, Louise Whiteley

Installation and material elements: Amanda Baum and Rose Leahy

Menu development: Kim Wejendorp and Josh Evans

Script writing: Amanda Baum, Rose Leahy, Josh Evans, and Louise Whiteley

Menu execution: Kim Wejendorp

Performance: Amanda Baum, Rose Leahy, Josh Evans, and Louise Whiteley

Curator: Louise Whiteley

Conceptual and scientific input: Rob Dunn and Joana Formosinho

Project coordinators: Cecilie Glerup and Simone Cecilie Pedersen

Co-creating assistants: Ella Yolande and Lene Rottensten

Menu execution assistant: Nurdin Topham

Creative producer: Anna Firbank

Soundscape: Sofie Birch (main room), Ella Yolande (anteroom)

Biomaterials: Natural Material Studio

Custom glass bowls: Adam Aaronson

Photos: Rune Svenningsen, Tobias Horvath, Josh Evans

Video: Tobias Horvath

Special thanks: Adam Bencard, Caroline Kothe

The project was supported by the Velux grant “Microbes on the Mind”, the Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research (CBMR) at the University of Copenhagen, Sustainable Food Innovation at The Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Biosustainability (DTU Biosustain), and Statens Kunstfond.